“At Your Cervix”: Screening & Treatment of a Shortened Cervix during Pregnancy

Balancing clinical care that is evidence-based with interventions to improve outcome and avoid harmful interventions is truly challenging when the finding of a shortened cervix on  transvaginal ultrasound evaluation is noted (i.e. Defined ≤ 25 mm). It is possible to counsel and treat women using the best data available combined with clinical experience regarding utilization of pessaries, cerclage, and progestogens/progesterone while acknowledging the uncertainties regarding efficacy. It is virtually certain that one singular approach to the management of preterm birth prevention will not be universally effective. Conflicting data presented on these interventions may be secondary to meaningful population differences, underpowered analysis despite the prospective controlled randomization often touted as the gold standard of medical literature, and variation in treatment protocols.

transvaginal ultrasound evaluation is noted (i.e. Defined ≤ 25 mm). It is possible to counsel and treat women using the best data available combined with clinical experience regarding utilization of pessaries, cerclage, and progestogens/progesterone while acknowledging the uncertainties regarding efficacy. It is virtually certain that one singular approach to the management of preterm birth prevention will not be universally effective. Conflicting data presented on these interventions may be secondary to meaningful population differences, underpowered analysis despite the prospective controlled randomization often touted as the gold standard of medical literature, and variation in treatment protocols.

Normally, cervical length is stable between 14 and 28 weeks of gestation and is described by a bell-shaped curve. For singleton gestations at about 20 weeks of gestation without a prior spontaneous preterm birth, the centiles for three common cervical length thresholds are approximately:

- 15 mm – 0.5thcentile

- 20 mm – 1stcentile

- 25 mm – 2ndto 3rdcentile

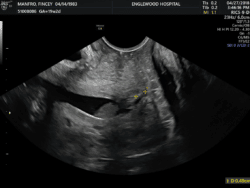

Cervical length is not significantly affected by parity, race/ethnicity, or maternal height. We perform universal cervical length screening based, in part, on a large study in which the introduction of universal cervical length screening in singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth was associated with a significant decrease in the frequency of preterm birth <37 weeks of gestation, <34 weeks, and <32 weeks, and the reduction was primarily due to a reduction in spontaneous preterm births (Son M Et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016). We measure cervical length transabdominally during the second-trimester fetal anatomic survey ultrasound in patients who are thought to be at low risk of preterm birth– if the cervix is short (defined as ≤ 35mm) or is not adequately seen, then a transvaginal ultrasound examination is performed for a definitive measurement. All women with risk factors for preterm birth undergo transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening.

At Carnegie Imaging for Women, we assess the patient’s prior obstetrical and gynecologic history and current pregnancy risk factors when recommendations for interventions are advised. At this time, OUR current guidelines include the following recommendations:

- Patient with a prior history of a singleton preterm birth currently with a singleton gestation

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm already on 17OHP prior to 24 weeks

- Advise ultrasound-indicated cerclage placement

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm already on 17OHP 24-28 weeks

- Advise Pessary placement

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm already on 17OHP prior to 24 weeks

- Patient with NO prior preterm birth with a singleton gestation and an incidental finding

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm between 16- 28 weeks

- Rx vaginal progesterone 200 mg per vagina qhs

- IF progressive shortening ≤ 15-20 mm 16-28weeks

- Place pessary (Saccone G, et al JAMA 2017)

- IF progressive shortening ≤ 5-10 mm 16-24 weeks

- Examine patient and, if dilated, recommend exam-indicated cerclage if not contracting and no signs of infection.

- Consider ultrasound-indicated cerclage placement on a case-by-case basis (Berghella V, et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynceol 2017), based on the actual cervical length, the gestational age, the change in length over time, and other risk factors.

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm between 16- 28 weeks

- Patient with a twin gestation and no prior preterm births

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm between 16- 28 weeks

- Rx vaginal progesterone 200 mg per vagina qhs

- IF progressive shortening ≤ 15-20 mm 16-28weeks

- Place pessary

- IF progressive shortening ≤ 5 mm 16-24 weeks

- Examine patient and, if dilated, place exam indicated cerclage if not contracting and no signs of infection.

- Cervical length ≤ 25 mm between 16- 28 weeks

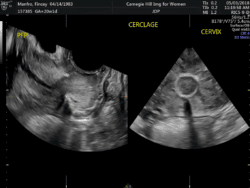

The two most common transvaginal techniques for cerclage were described by Shirodkar and McDonald; modifications of both procedures have also been described. Our preference is to  perform the Shirodkar procedure– however, no randomized trial has compared the McDonald and Shirodkar procedures directly. One study observed McDonald and Shirodkar procedures had similar obstetric outcomes in patients undergoing their first cerclage, but higher birth weight when Shirodkar rather than McDonald cerclage was performed for the second procedure (3020 and 2470 grams, respectively) (Treadwell MC, et al AJOG 1991). Our own published experience compared the efficacy of Shirodkar to McDonald cerclage in patients with singleton pregnancies undergoing an ultrasound-indicated cerclage. Shirodkar was associated with later GA at delivery (36.98 vs. 33.34 weeks), a higher likelihood of delivering ≥35 weeks (83 vs. 55.6%) and ≥32 weeks (91.5 vs. 59.3%), and a lower likelihood of preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM) (13.0 vs. 46.2%). On adjusted analysis Shirodkar remained significantly associated with an increased incidence of delivery ≥32 weeks (OR 5.18). (Hume H, et al J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012)

perform the Shirodkar procedure– however, no randomized trial has compared the McDonald and Shirodkar procedures directly. One study observed McDonald and Shirodkar procedures had similar obstetric outcomes in patients undergoing their first cerclage, but higher birth weight when Shirodkar rather than McDonald cerclage was performed for the second procedure (3020 and 2470 grams, respectively) (Treadwell MC, et al AJOG 1991). Our own published experience compared the efficacy of Shirodkar to McDonald cerclage in patients with singleton pregnancies undergoing an ultrasound-indicated cerclage. Shirodkar was associated with later GA at delivery (36.98 vs. 33.34 weeks), a higher likelihood of delivering ≥35 weeks (83 vs. 55.6%) and ≥32 weeks (91.5 vs. 59.3%), and a lower likelihood of preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM) (13.0 vs. 46.2%). On adjusted analysis Shirodkar remained significantly associated with an increased incidence of delivery ≥32 weeks (OR 5.18). (Hume H, et al J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012)

Different additional strategies have been adopted for the prevention of preterm birth including lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, diet, aerobic exercise, and various nutritional supplements (e.g. omega-3 fatty acids, folic acid supplementation). Most have abandoned use of prophylactic bedrest, intravenous hydration, and pelvic rest, given the absence of data suggesting benefit and the potential risks involved (e.g. thromboembolism, fluid overload). In the setting of a shortened cervix with either a cerclage or pessary in place, we advise pelvic rest, though we inform patients this is clearly not an evidence-based practice. We have continued 17OHP or vaginal progesterone therapy on patients who undergo cerclage placement if they had already been placed on it prior to the surgery.

Preterm labor is an extremely difficult condition to study, given the complex pathways leading to the final untoward event. We continue to critically assess our management approaches to determine if various treatments affect each other and whether they act synergistically, redundantly, or even result in less efficacy when used in combination. While at times we may all feel compelled to do almost anything possible that might reduce the impending risk of preterm birth, MFMs at Carnegie Imaging for Women try to avoid “indication creep” with overutilization of various treatment.

Carnegie Imaging for Women blogs are intended for educational purposes only and do not replace certified professional care. Medical conditions vary and change frequently. Please ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding your condition to receive a proper diagnosis or risk analysis. Thank you!

Contact Us

Contact Us

Contact Us

Contact Us Carnegie South

Carnegie South